Senin, 10 Juni 2013

task-based instruction ( TBI)

task-based instruction (TBI)

focuses on the use of authentic language and on asking students to do

meaningful tasks using the target language. Such tasks can include visiting a

doctor, conducting an interview, or calling customer service for help.

Assessment is primarily based on task outcome (in other words the appropriate

completion of real world tasks) rather than on accuracy of prescribed language

forms. This makes TBLL especially popular for developing target language

fluency and student confidence. As such TBLL can be considered a branch ofCommunicative Language Teaching (CLT).

In practice

The core of the lesson or project is, as the

name suggests, the task. Teachers and curriculum developers should bear in mind

that any attention to form, i.e. grammar or vocabulary, increases the

likelihood that learners may be distracted from the task itself and become

preoccupied with detecting and correcting errors and/or looking up language in

dictionaries and grammar references. Although there may be several effective

frameworks for creating a task-based learning lesson, here is a basic outline:

Pre-task

In the pre-task, the teacher will present what will be expected of the

students in the task phase. Additionally, in the "weak" form of TBLL,

the teacher may prime the students with key vocabulary or grammatical

constructs, although this can mean that the activity is, in effect, more

similar to the more traditional present-practise-produce (PPP) paradigm. In

"strong" task-based learning lessons, learners are responsible for

selecting the appropriate language for any given context themselves. The

instructor may also present a model of the task by either doing it themselves

or by presenting picture, audio, or video demonstrating the task.

Task

During the task phase, the students perform the task, typically in small

groups, although this is dependent on the type of activity. And unless the

teacher plays a particular role in the task, then the teacher's role is

typically limited to one of an observer or counselor—thus the reason for it

being a more student-centered methodology.

Review

If learners have created tangible linguistic products, e.g. text,

montage, presentation, audio or video recording, learners can review each

others' work and offer constructive feedback. If a task is set to extend over

longer periods of time, e.g. weeks, and includes iterative cycles of

constructive activity followed by review, TBLL can be seen as analogous to Project-based learning

Theory of multiple intelligences

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

This article is about Howard Gardner's theory of multiple intelligences. For other uses, see Intelligence.

The theory of multiple intelligences was proposed by Howard Gardner in his 1983 book Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences as a model of intelligence that differentiates it into specific (primarily sensory) "modalities", rather than seeing it as dominated by a single general ability.

Gardner argues that there is a wide range of cognitive abilities, and that there are only very weak correlations among them. For example, the theory postulates that a child who learns to multiply easily is not necessarily more intelligent than a child who has more difficulty on this task. The child who takes more time to master multiplication may best learn to multiply through a different approach, may excel in a field outside mathematics, or may be looking at and understanding the multiplication process at a fundamentally deeper level. Such a fundamental understanding can result in slowness and can hide a mathematical intelligence potentially higher than that of a child who quickly memorizes the multiplication table despite possessing a shallower understanding of the process of multiplication.

Intelligence tests and psychometrics have generally found high correlations between different aspects of intelligence, rather than the low correlations which Gardner's theory predicts, supporting the prevailing theory of general intelligence rather than multiple intelligences (MI). The theory has been widely criticized by mainstream psychology for its lack of empirical evidence, and its dependence on subjective judgement. Certain models of alternative education employ the approaches suggested by the theory.

The multiple intelligences

Gardner articulated seven criteria for a behavior to be considered an intelligence.[ These were that the intelligences showed:- Potential for brain isolation by brain damage,

- Place in evolutionary history,

- Presence of core operations,

- Susceptibility to encoding (symbolic expression),

- A distinct developmental progression,

- The existence of savants, prodigies and other exceptional people,

- Support from experimental psychology and psychometric findings.

Logical-mathematical

This area has to do with logic, abstractions, reasoning and numbers and critical thinking. This also has to do with having the capacity to understand the underlying principles of some kind of causal system. Logical reasoning is closely linked to fluid intelligence and to general intelligence (g factor).Spatial

Main article: Spatial intelligence (psychology)

This area deals with spatial judgment and the ability to visualize

with the mind's eye. Spatial ability is one of the three factors beneath

g in the hierarchical model of intelligence.Linguistic

People with high verbal-linguistic intelligence display a facility with words and languages. They are typically good at reading, writing, telling stories and memorizing words along with dates. Verbal ability is one of the most g-loaded abilities.This type of intelligence is associated with the Verbal IQ in WAIS-III.Bodily-kinesthetic

Main article: Kinesthetic learning

The core elements of the bodily-kinesthetic

intelligence are control of one's bodily motions and the capacity to

handle objects skillfully. Gardner elaborates to say that this also

includes a sense of timing, a clear sense of the goal of a physical

action, along with the ability to train responses.People who have bodily-kinesthetic intelligence should learn better by involving muscular movement (e.g. getting up and moving around into the learning experience), and be generally good at physical activities such as sports, dance, acting, and making things.

Gardner believes that careers that suit those with this intelligence include: athletes, pilots, dancers, musicians, actors, surgeons, builders, police officers, and soldiers. Although these careers can be duplicated through virtual simulation, they will not produce the actual physical learning that is needed in this intelligence.

Musical

Further information: auditory learning

This area has to do with sensitivity to sounds, rhythms, tones, and music. People with a high musical intelligence normally have good pitch and may even have absolute pitch,

and are able to sing, play musical instruments, and compose music.

Since there is a strong auditory component to this intelligence, those

who are strongest in it may learn best via lecture. They will sometimes

use songs or rhythms to learn. They have sensitivity to rhythm, pitch,

meter, tone, melody or timbre.Interpersonal

This area has to do with interaction with others. In theory, individuals who have high interpersonal intelligence are characterized by their sensitivity to others' moods, feelings, temperaments and motivations, and their ability to cooperate in order to work as part of a group. According to Gardner in How Are Kids Smart: Multiple Intelligences in the Classroom, "Inter- and Intra- personal intelligence is often misunderstood with being extroverted or liking other people..." Those with this intelligence communicate effectively and empathize easily with others, and may be either leaders or followers. They typically learn best by working with others and often enjoy discussion and debate.Gardner believes that careers that suit those with this intelligence include sales, politicians, managers, teachers, counselors and social workers

Intrapersonal

This area has to do with introspective and self-reflective capacities. This refers to having a deep understanding of the self; what your strengths/ weaknesses are, what makes you unique, being able to predict your own reactions/emotions.Naturalistic

This area has to do with nurturing and relating information to one’s natural surroundings. Examples include classifying natural forms such as animal and plant species and rocks and mountain types. This ability was clearly of value in our evolutionary past as hunters, gatherers, and farmers; it continues to be central in such roles as botanist or chef.Existential

Some proponents of multiple intelligence theory proposed spiritual or religious intelligence as a possible additional type. Gardner did not want to commit to a spiritual intelligence, but suggested that an "existential" intelligence may be a useful construct.he hypothesis of an existential intelligence has been further explored by educational researchers.Critical reception

Definition of intelligence

One major criticism of the theory is that it is ad hoc: that Gardner is not expanding the definition of the word "intelligence", but rather denies the existence of intelligence as traditionally understood, and instead uses the word "intelligence" where other people have traditionally used words like "ability" and "aptitude". This practice has been criticized by Robert J. Sternberg,] Eysenck, and Scarr.] White (2006) points out that Gardner's selection and application of criteria for his "intelligences" is subjective and arbitrary, and that a different researcher would likely have come up with different criteria.Defenders of MI theory argue that the traditional definition of intelligence is too narrow, and thus a broader definition more accurately reflects the differing ways in which humans think and learn. They would state that the traditional interpretation of intelligence collapses under the weight of its own logic and definition, noting that intelligence is usually defined as the cognitive or mental capacity of an individual, which by logical necessity would include all forms of mental qualities, not just the ones most transparent to I.Q. tests.

Some criticisms arise from the fact that Gardner has not provided a test of his multiple intelligences. He originally defined it as the ability to solve problems that have value in at least one culture, or as something that a student is interested in. He then added a disclaimer that he has no fixed definition, and his classification is more of an artistic judgment than fact:

Gardner argues that by calling linguistic and logical-mathematical abilities intelligences, but not artistic, musical, athletic, etc. abilities, the former are needlessly aggrandized. Certain critics balk at this widening of the definition, saying that it ignores "the connotation of intelligence ... [which] has always connoted the kind of thinking skills that makes one successful in school."Ultimately, it would certainly be desirable to have an algorithm for the selection of an intelligence, such that any trained researcher could determine whether a candidate's intelligence met the appropriate criteria. At present, however, it must be admitted that the selection (or rejection) of a candidate's intelligence is reminiscent more of an artistic judgment than of a scientific assessment.

Gardner writes "I balk at the unwarranted assumption that certain human abilities can be arbitrarily singled out as intelligence while others cannot." Critics hold that given this statement, any interest or ability can be redefined as "intelligence". Thus, studying intelligence becomes difficult, because it diffuses into the broader concept of ability or talent. Gardner's addition of the naturalistic intelligence and conceptions of the existential and moral intelligences are seen as fruits of this diffusion. Defenders of the MI theory would argue that this is simply a recognition of the broad scope of inherent mental abilities, and that such an exhaustive scope by nature defies a one-dimensional classification such as an IQ value.

The theory and definitions have been critiqued by Perry D. Klein as being so unclear as to be tautologous and thus unfalsifiable. Having a high musical ability means being good at music while at the same time being good at music is explained by having a high musical ability.

Neo-Piagetian criticism

Andreas Demetriou suggests that theories which overemphasize the autonomy of the domains are as simplistic as the theories that overemphasize the role of general intelligence and ignore the domains. He agrees with Gardner that there are indeed domains of intelligence that are relevantly autonomous of each other.Some of the domains, such as verbal, spatial, mathematical, and social intelligence are identified by most lines of research in psychology. In Demetriou's theory, one of the neo-Piagetian theories of cognitive development, Gardner is criticized for underestimating the effects exerted on the various domains of intelligences by processes that define general processing efficiency, such as speed of processing, executive functions, working memory, and meta-cognitive processes underlying self-awareness and self-regulation. All of these processes are integral components of general intelligence that regulate the functioning and development of different domains of intelligence.The domains are to a large extent expressions of the condition of the general processes, and may vary because of their constitutional differences but also differences in individual preferences and inclinations. Their functioning both channels and influences the operation of the general processes. Thus, one cannot satisfactorily specify the intelligence of an individual or design effective intervention programs unless both the general processes and the domains of interest are evaluated.

IQ tests

Gardner argues that IQ tests only measures linguistic and logical-mathematical abilities. Psychologist Alan S. Kaufman points out that IQ tests have measured spatial abilities for 70 years.[27] Modern IQ tests are greatly influenced by the Cattell-Horn-Carroll theory which incorporates a general intelligence but also many more narrow abilities. While IQ tests do give an overall IQ score, they now also give scores for many more narrow abilities.[27]Lack of empirical evidence

According to a 2006 study many of Gardner's "intelligences" correlate with the g factor, supporting the idea of a single dominant type of intelligence. According to the study, each of the domains proposed by Gardner involved a blend of g, of cognitive abilities other than g, and, in some cases, of non-cognitive abilities or of personality characteristics.ued that thousands of studies support the importance of intelligence quotient (IQ) in predicting school and job performance, and numerous other life outcomes. In contrast, empirical support for non-g intelligences is lacking or very poor. She argued that despite this the ideas of multiple non-g intelligences are very attractive to many due to the suggestion that everyone can be smart in some way.[29]A critical review of MI theory argues that there is little empirical evidence to support it:

The same review presents evidence to demonstrate that cognitive neuroscience research does not support the theory of multiple intelligences:To date there have been no published studies that offer evidence of the validity of the multiple intelligences. In 1994 Sternberg reported finding no empirical studies. In 2000 Allix reported finding no empirical validating studies, and at that time Gardner and Connell conceded that there was "little hard evidence for MI theory" (2000, p. 292). In 2004 Sternberg and Grigerenko stated that there were no validating studies for multiple intelligences, and in 2004 Gardner asserted that he would be "delighted were such evidence to accrue"nd admitted that "MI theory has few enthusiasts among psychometricians or others of a traditional psychological background" because they require "psychometric or experimental evidence that allows one to prove the existence of the several intelligences.

Several articles have surveyed the use of Gardner's ideas and conclude that there is little to no academically substantiated evidence that his ideas work in practice. Steven A. Stahl found that most of the previous studies which claimed to show positive results had major flaws:... the human brain is unlikely to function via Gardner’s multiple intelligences. Taken together the evidence for the intercorrelations of subskills of IQ measures, the evidence for a shared set of genes associated with mathematics, reading, and g, and the evidence for shared and overlapping "what is it?" and "where is it?" neural processing pathways, and shared neural pathways for language, music, motor skills, and emotions suggest that it is unlikely that each of Gardner’s intelligences could operate "via a different set of neural mechanisms" (1999, p. 99). Equally important, the evidence for the "what is it?" and "where is it?" processing pathways, for Kahneman’s two decision-making systems, and for adapted cognition modules suggests that these cognitive brain specializations have evolved to address very specific problems in our environment. Because Gardner claimed that the intelligences are innate potentialities related to a general content area, MI theory lacks a rationale for the phylogenetic emergence of the intelligences.

The theory of multiple intelligences has been widely used as an example of pseudoscience, because it lacks empirical evidence or falsifiability.Among others, Marie Carbo claims that her learning styles work is based on research. (I discuss Carbo because she publishes extensively on her model and is very prominent in the workshop circuit ...) But given the overwhelmingly negative findings in the published research, I wondered what she was citing, and about a decade ago, I thought it would be interesting to take a look. Reviewing her articles, I found that out of 17 studies she had cited, only one was published. Fifteen were doctoral dissertations and 13 of these came out of one university—St. John’s University in New York, Carbo’s alma mater. None of these had been in a peer-refereed journal. When I looked closely at the dissertations and other materials, I found that 13 of the 17 studies that supposedly support her claim had to do with learning styles based on something other than modality.

Use in education

Gardner defines an intelligence as "biopsychological potential to process information that can be activated in a cultural setting to solve problems or create products that are of value in a culture. According to Gardner, there are more ways to do this than just through logical and linguistic intelligence. Gardner believes that the purpose of schooling "should be to develop intelligences and to help people reach vocational and avocational goals that are appropriate to their particular spectrum of intelligences. People who are helped to do so, [he] believe[s], feel more engaged and competent and therefore more inclined to serve society in a constructive way.Gardner contends that IQ tests focus mostly on logical and linguistic intelligence. Upon doing well on these tests, the chances of attending a prestigious college or university increase, which in turn creates contributing members of society. While many students function well in this environment, there are those who do not. According to Helding (2009), "Standard IQ tests measure knowledge gained at a particular moment in time, they can only provide a freeze-frame view of crystallized knowledge. They cannot assess or predict a person’s ability to learn, to assimilate new information, or to solve new problems. Gardner's theory argues that students will be better served by a broader vision of education, wherein teachers use different methodologies, exercises and activities to reach all students, not just those who excel at linguistic and logical intelligence. It challenges educators to find "ways that will work for this student learning this topic".

James Traub's article in The New Republic notes that Gardner's system has not been accepted by most academics in intelligence or teaching. Gardner states that "while Multiple Intelligences theory is consistent with much empirical evidence, it has not been subjected to strong experimental tests ... Within the area of education, the applications of the theory are currently being examined in many projects. Our hunches will have to be revised many times in light of actual classroom experience.

George Miller, a prominent cognitive psychologist, wrote in The New York Times Book Review that Gardner's argument consisted of "hunch and opinion". Jerome Bruner called Gardner’s "intelligences" "at best useful fictions," and Charles Murray and Richard J. Herrnstein in The Bell Curve (1994) called Gardner's theory "uniquely devoid of psychometric or other quantitative evidence."

Thomas Armstrong argues that Waldorf education engages all of Gardner's original seven intelligences. In spite of its lack of general acceptance in the psychological community, Gardner's theory has been adopted by many schools, where it is often used to underpin discussion about learning styles, and hundreds of books have been written about its applications in education.Gardner himself has said he is "uneasy" with the way his theory has been used in education. The No Child Left Behind test legislation in the United States does not encompass the multiple intelligences framework in the exams' design or implementatio

Grammar-translation method

The grammar-translation method is a method of teaching foreign languages derived from the classical (sometimes called traditional) method of teaching Greek and Latin. In grammar-translation classes, students learn grammatical rules and then apply those rules by translating sentences between the target language and their native language. Advanced students may be required to translate whole texts word-for-word. The method has two main goals: to enable students to read and translate literature written in the target language, and to further students’ general intellectual development.

Throughout Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, the education system was formed primarily around a concept called faculty psychology. This theory dictated that the body and mind were separate and the mind consisted of three parts: the will, emotion, and intellect. It was believed that the intellect could be sharpened enough to eventually control the will and emotions. The way to do this was through learning classical literature of the Greeks and Romans, as well as mathematics.[citation needed] Additionally, an adult with such an education was considered mentally prepared for the world and its challenges.

At first it was believed that teaching modern languages was not useful for the development of mental discipline and thus they were left out of the curriculum.[citation needed] When modern languages did begin to appear in school curricula in the 19th century, teachers taught them with the same grammar-translation method as was used for classical Latin and Greek. As a result, textbooks were essentially copied for the modern language classroom. In the United States of America, the basic foundations of this method were used in most high school and college foreign language classrooms.

There is not usually any listening or speaking practice, and very little attention is placed on pronunciation or any communicative aspects of the language. The skill exercised is reading, and then only in the context of translation.

According to Richards and Rodgers, the grammar-translation has been rejected as a legitimate language teaching method by modern scholars:

History and philosophy

The grammar-translation method originated from the practice of teaching Latin. In the early 1500s, Latin was the most widely-studied foreign language due to its prominence in government, academia, and business.However, during the course of the century the use of Latin dwindled, and it was gradually replaced by English, French, and Italian. After the decline of Latin, the purpose of learning it in schools changed. Whereas previously students had learned Latin for the purpose of communication, it came to be learned as a purely academic subject.Throughout Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, the education system was formed primarily around a concept called faculty psychology. This theory dictated that the body and mind were separate and the mind consisted of three parts: the will, emotion, and intellect. It was believed that the intellect could be sharpened enough to eventually control the will and emotions. The way to do this was through learning classical literature of the Greeks and Romans, as well as mathematics.[citation needed] Additionally, an adult with such an education was considered mentally prepared for the world and its challenges.

At first it was believed that teaching modern languages was not useful for the development of mental discipline and thus they were left out of the curriculum.[citation needed] When modern languages did begin to appear in school curricula in the 19th century, teachers taught them with the same grammar-translation method as was used for classical Latin and Greek. As a result, textbooks were essentially copied for the modern language classroom. In the United States of America, the basic foundations of this method were used in most high school and college foreign language classrooms.

Principles and goals

There are two main goals to grammar-translation classes. One is to develop students’ reading ability to a level where they can read literature in the target language. [The other is to develop students’ general mental discipline. The users of foreign language wanted simply to note things of their interest in the literature of foreign languages. Therefore, this method focuses on reading and writing and has developed techniques which facilitate more or less the learning of reading and writing only. As a result, speaking and listening are overlooked.Method

Grammar-translation classes are usually conducted in the students’ native language. Grammar rules are learned deductively; students learn grammar rules by rote, and then practice the rules by doing grammar drills and translating sentences to and from the target language. More attention is paid to the form of the sentences being translated than to their content. When students reach more advanced levels of achievement, they may translate entire texts from the target language. Tests often consist of the translation of classical texts.There is not usually any listening or speaking practice, and very little attention is placed on pronunciation or any communicative aspects of the language. The skill exercised is reading, and then only in the context of translation.

Materials

The mainstay of classroom materials for the grammar-translation method is the textbook. Textbooks in the 19th century attempted to codify the grammar of the target language into discrete rules for students to learn and memorize. A chapter in a typical grammar-translation textbook would begin with a bilingual vocabulary list, after which there would be grammar rules for students to study and sentences for them to translate.[1] Some typical sentences from 19th-century textbooks are as follows:The philosopher pulled the lower jaw of the hen.

My sons have bought the mirrors of the Duke.

The cat of my aunt is more treacherous than the dog of your uncle.[3]

Reception

The method by definition has a very limited scope. Because speaking or any kind of spontaneous creative output was missing from the curriculum, students would often fail at speaking or even letter writing in the target language. A noteworthy quote describing the effect of this method comes from Bahlsen, who was a student of Plötz, a major proponent of this method in the 19th century. In commenting about writing letters or speaking he said he would be overcome with "a veritable forest of paragraphs, and an impenetrable thicket of grammatical rules."[4]According to Richards and Rodgers, the grammar-translation has been rejected as a legitimate language teaching method by modern scholars:

[T]hough it may be true to say that the Grammar-Translation Method is still widely practiced, it has no advocates. It is a method for which there is no theory. There is no literature that offers a rationale or justification for it or that attempts to relate it to issues in linguistics, psychology, or educational theory.

WHOLE LANGUAGE

Whole language describes a literacy philosophy which

emphasizes that children should focus on meaning and strategy

instruction. It is often contrasted with phonics-based

methods of teaching reading and writing which emphasize instruction for

decoding and spelling. However, from whole language practitioners'

perspective, this view is erroneous and sets up a false dichotomy. Whole

language practitioners teach to develop a knowledge of language

including the graphophonic, syntactic, semantic and pragmatic aspects of

language. Within a whole language perspective, language is treated as a

complete meaning-making system, the parts of which function in

relational ways. It has drawn criticism by those who advocate "back to basics" pedagogy or reading instruction because whole language is based on a limited body of scientific research.

Whole language is an educational philosophy that is complex to describe, particularly because it is informed by multiple research fields including but not limited to education, linguistics, psychology, sociology, and anthropology (see also Language Experience Approach). Several strands run through most descriptions of whole language:

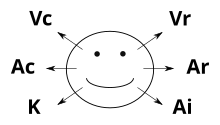

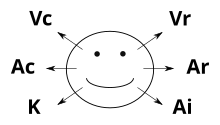

Goodman thought that there are four "cueing systems" for reading, four things that readers have to guess what word comes next:

The graphophonemic cues are related to the sounds we hear (the phonological system including individual letters and letter combinations), the letters of the alphabet, and the conventions of spelling, punctuation and print. Students who are emerging readers use these cues considerably. However, in the English language there is a very imprecise relationship between written symbols and sound symbols.[7] Sometimes the relationships and their patterns do not work, as in the example of great and head. Proficient readers and writers draw on their prior experiences with text and the other cueing systems, as well as the phonological system, as their reading and writing develops. Ken Goodman writes that, "The cue systems are used simultaneously and interdependently. What constitutes useful graphic information depends on how much syntactic and semantic information is available. Within high contextual constraints an initial consonant may be all that is needed to identify an element and make possible the prediction of an ensuing sequence or the confirmation of prior predictions."[8] He continues with, "Reading requires not so much skills as strategies that make it possible to select the most productive cues." He believes that reading involves the interrelationship of all the language systems. Readers sample and make judgments about which cues from each system will provide the most useful information in making predictions that will get them to meaning. Goodman[8] provides a partial list of the various systems readers use as they interact with text. Within the graphophonemic system there are:

The semantic system is developed from the beginning through early interactions with adults. At first, this usually involves labeling (e.g. This is a dog). Then labeling becomes more detailed (e.g., It is a Labrador dog. Its coat is black.) The child learns that there is a set of "dog attributes" and that within the category "dog", there are subsets of "dog" (e.g. long-hair, short-hair). The development of this system and the development of the important concepts that relate to the system are largely accomplished as children begin to explore language independently. As children speak about what they’ve done and play out their experiences, they are making personal associations between their experiences and language. This is critical to success in later literacy practices such as reading comprehension and writing. The meaning people bring to the reading is available to them through every cuing system, but it’s particularly influential as we move from our sense of the syntactic patterns to the semantic structures.[8]

To support the reader in developing the semantic system, ask, "Does that make sense"?

The syntactic system, according to Goodman and Watson,[7] includes the interrelation of words and sentences within connected text. In the English language, syntactic relations include word order, tense, number, and gender. The syntactic system is also concerned with word parts that change the meaning of a word, called morphemes. For example, adding the suffix "less" or adding "s" to the end of a word changes its meaning or tense. As speakers of English, people know where to place subjects, which pronoun to use and where adjectives occur. Individual word meaning is determined by the place of the word in the sentence and the particular semantic or syntactic role it occupies.[10] For example: The mayor was present when he received a beautiful present from the present members of the board.

The syntactic system is usually in place when children begin school. Immersed in language, children begin to recognize that phrases and sentences are usually ordered in certain ways. This notion of ordering is the development of syntax. Like all the cueing systems, syntax provides the possibility of correct prediction when trying to make sense or meaning of written language. Goodman notes the cues found in the flow of language are:[8]

The pragmatic system is also involved in the construction of meaning while reading. This brings into play the socio-cultural knowledge of the reader. It provides information about the purposes and needs the reader has while reading. Yetta Goodman and Dorothy Watson state that, "Language has different meaning depending on the reason for use, the circumstances in which the language is used, and the ideas writers and readers have about the contextual relations with the language users. Language cannot exist outside a sociocultural context, which includes the prior knowledge of the language user. For example, shopping lists, menus, reports and plays are arranged uniquely and are dependent on the message, the intent, the audience, and the context."[7]

By the time children begin school, they may have developed an inferred understanding of some of the pragmatics of a particular situation. For example, turn taking in conversation, reading poetry or a shopping list. "While different materials may share common semantic, syntactic, and graphophonic features, each genre has its own organization and each requires certain experiences by the reader."[7]

To support the reader in developing the pragmatic system ask, "What is the purpose and function of this literacy event?"

Goodman performed a study where children first read words individually, and then read the same words in connected text. He found that the children did better when they read the words in connected text. Later replications of the experiment failed to find effects, however, when children did not read the same words in connected text immediately after reading them individually, as they had in Goodman's experiment.[11][12]

Goodman's theory has been criticized by other researchers who favor a phonics-based approach, and present research to support their viewpoint. Critics argue that good readers use decoding as their primary approach to reading, and use context to confirm that what they have read makes sense.

Most whole language advocates see that children go through stages of spelling development as they develop, use and gain control over written language. Early literacy research conducted by Piagetian researcher, Emilia Ferreiro and published in her landmark book, Literacy Before Schooling, has been replicated by University of Alabama professor, Maryann Manning. Based on this research "invented spelling" is another "whole-part-whole" approach: children learn to read by writing in a meaningful context, e.g. by writing letters to others. To write a word they have to decompose its spoken form into sounds and then to translate them into letters, e.g. k, a, t for the phonemes /k/, /æ/, and /t/. Empirical studies[14] show that later orthographic development is fostered rather than hindered by these invented spellings - as long as children from the beginning are confronted with "book spellings", too.

In December 2005 the Australian Government endorsed the teaching of synthetic phonics, and discredited the whole language approach ("on its own"). Its Department of Education, Science and Training published a National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy. [1] The report states "The evidence is clear, whether from research, good practice observed in schools, advice from submissions to the Inquiry, consultations, or from Committee members’ own individual experiences, that direct systematic instruction in phonics during the early years of schooling is an essential foundation for teaching children to read." Pg 11. See Synthetic phonics#Acceptance in Australia

No Child Left Behind has brought a resurgence of interest in phonics. Whole language has thus during the 2000s receded from being the dominant reading model in the education field to marginal status, and it continues to fade.

Whole language is an educational philosophy that is complex to describe, particularly because it is informed by multiple research fields including but not limited to education, linguistics, psychology, sociology, and anthropology (see also Language Experience Approach). Several strands run through most descriptions of whole language:

- focus on making meaning in reading and expressing meaning in writing;

- constructivist approaches to knowledge creation, emphasizing students' interpretations of text and free expression of ideas in writing (often through daily journal entries);

- emphasis on high-quality and culturally-diverse literature;

- integrating literacy into other areas of the curriculum, especially math, science, and social studies;

- frequent reading

- with students in small "guided reading" groups

- to students with "read alouds"

- by students independently;

- reading and writing for real purposes;

- focus on motivational aspects of literacy, emphasizing the love of books and engaging reading materials;

- meaning-centered whole to part to whole instruction where phonics are taught contextually in "embedded" phonics (different from Synthetic phonics or Analytical phonics); and

- emphasis on using and understanding the meaning-making role of phonics, grammar, spelling, capitalization and punctuation in diverse social contexts.

- Sub-lexical reading

- Lexical reading

Learning theory

The idea of "whole" language has its basis in a range of theories of learning related to the epistemologies called "holism". Holism is based upon the belief that it is not possible to understand learning of any kind by analyzing small chunks of the learning system. Holism was very much a response to behaviorism, which emphasized that the world could be understood by experimenting with stimuli and responses. Holists considered this a reductionist perspective that did not recognize that "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts." Analyzing individual behaviors, holists argued, could never tell us how the entire human mind worked. This is—in simplified terms—the theoretical basis for the term "whole language."[citation needed]Chomsky and Goodman

The whole language approach to phonics grew out of Noam Chomsky's ideas about language acquisition. In 1967, Ken Goodman had an idea about reading, which he considered similar to Chomsky's, and he wrote a widely-cited article calling reading a "psycholinguistic guessing game". He chided educators for attempting to apply what he saw as unnecessary orthographic order to a process that relied on holistic examination of words.[6]Goodman thought that there are four "cueing systems" for reading, four things that readers have to guess what word comes next:

- graphophonemic: the shapes of the letters, and the sounds that they evoke (see phonetics).

- semantic: what word one would expect to occur based on the meaning of the sentence so far (see semantics).

- syntactic: what part of speech or word would make sense based on the grammar of the language (see syntax).

- pragmatic: what is the function of the text

The graphophonemic cues are related to the sounds we hear (the phonological system including individual letters and letter combinations), the letters of the alphabet, and the conventions of spelling, punctuation and print. Students who are emerging readers use these cues considerably. However, in the English language there is a very imprecise relationship between written symbols and sound symbols.[7] Sometimes the relationships and their patterns do not work, as in the example of great and head. Proficient readers and writers draw on their prior experiences with text and the other cueing systems, as well as the phonological system, as their reading and writing develops. Ken Goodman writes that, "The cue systems are used simultaneously and interdependently. What constitutes useful graphic information depends on how much syntactic and semantic information is available. Within high contextual constraints an initial consonant may be all that is needed to identify an element and make possible the prediction of an ensuing sequence or the confirmation of prior predictions."[8] He continues with, "Reading requires not so much skills as strategies that make it possible to select the most productive cues." He believes that reading involves the interrelationship of all the language systems. Readers sample and make judgments about which cues from each system will provide the most useful information in making predictions that will get them to meaning. Goodman[8] provides a partial list of the various systems readers use as they interact with text. Within the graphophonemic system there are:

- Letter-sound relationships

- Shape (or word configuration)

- Know ‘little words’ in bigger words

- Whole know words

- Recurrent spelling patterns

The semantic system is developed from the beginning through early interactions with adults. At first, this usually involves labeling (e.g. This is a dog). Then labeling becomes more detailed (e.g., It is a Labrador dog. Its coat is black.) The child learns that there is a set of "dog attributes" and that within the category "dog", there are subsets of "dog" (e.g. long-hair, short-hair). The development of this system and the development of the important concepts that relate to the system are largely accomplished as children begin to explore language independently. As children speak about what they’ve done and play out their experiences, they are making personal associations between their experiences and language. This is critical to success in later literacy practices such as reading comprehension and writing. The meaning people bring to the reading is available to them through every cuing system, but it’s particularly influential as we move from our sense of the syntactic patterns to the semantic structures.[8]

To support the reader in developing the semantic system, ask, "Does that make sense"?

The syntactic system, according to Goodman and Watson,[7] includes the interrelation of words and sentences within connected text. In the English language, syntactic relations include word order, tense, number, and gender. The syntactic system is also concerned with word parts that change the meaning of a word, called morphemes. For example, adding the suffix "less" or adding "s" to the end of a word changes its meaning or tense. As speakers of English, people know where to place subjects, which pronoun to use and where adjectives occur. Individual word meaning is determined by the place of the word in the sentence and the particular semantic or syntactic role it occupies.[10] For example: The mayor was present when he received a beautiful present from the present members of the board.

The syntactic system is usually in place when children begin school. Immersed in language, children begin to recognize that phrases and sentences are usually ordered in certain ways. This notion of ordering is the development of syntax. Like all the cueing systems, syntax provides the possibility of correct prediction when trying to make sense or meaning of written language. Goodman notes the cues found in the flow of language are:[8]

- Patterns of words (or function order)

- Inflection and inflectional agreement

- Function words such as noun markers (the, a, that)

- Intonation (which is poorly represented in writing by punctuation)

The pragmatic system is also involved in the construction of meaning while reading. This brings into play the socio-cultural knowledge of the reader. It provides information about the purposes and needs the reader has while reading. Yetta Goodman and Dorothy Watson state that, "Language has different meaning depending on the reason for use, the circumstances in which the language is used, and the ideas writers and readers have about the contextual relations with the language users. Language cannot exist outside a sociocultural context, which includes the prior knowledge of the language user. For example, shopping lists, menus, reports and plays are arranged uniquely and are dependent on the message, the intent, the audience, and the context."[7]

By the time children begin school, they may have developed an inferred understanding of some of the pragmatics of a particular situation. For example, turn taking in conversation, reading poetry or a shopping list. "While different materials may share common semantic, syntactic, and graphophonic features, each genre has its own organization and each requires certain experiences by the reader."[7]

To support the reader in developing the pragmatic system ask, "What is the purpose and function of this literacy event?"

Goodman performed a study where children first read words individually, and then read the same words in connected text. He found that the children did better when they read the words in connected text. Later replications of the experiment failed to find effects, however, when children did not read the same words in connected text immediately after reading them individually, as they had in Goodman's experiment.[11][12]

Goodman's theory has been criticized by other researchers who favor a phonics-based approach, and present research to support their viewpoint. Critics argue that good readers use decoding as their primary approach to reading, and use context to confirm that what they have read makes sense.

Application of Goodman's theory

Goodman's argument was compelling to educators as a way of thinking about beginning reading and literacy more broadly. This led to the idea that reading and writing were ideas that should be considered as wholes, learned by experience and exposure more than analysis and didactic instruction. This largely accounts for the focus on time spent reading, especially independent reading. Many classrooms (whole language or otherwise) include silent reading time, sometimes called DEAR ("Drop Everything And Read") time or SSR (sustained silent reading). Some versions of this independent reading time include a structured role for the teacher, especially Reader's Workshop. Despite the popularity of the extension of Chomsky's linguistic ideas to literacy, there is some neurological and experimental research that has concluded that reading, unlike language, is not a pre-programmed human skill. It must be learned. Dr. Sally Shaywitz,[13] a neurologist at Yale University, is credited with much of the research on the neurological structures of reading.Contrasts with phonics

Because of this holistic emphasis, whole language is contrasted with skill-based areas of instruction, especially phonics and synthetic phonics. Phonics instruction is a commonly-used technique for teaching students to read. Phonics instruction tends to emphasize attention to the individual components of words, for example, the phonemes /k/, /æ/, and /t/ are represented by the graphemes c, a, and t. Because they do not focus exclusively on the individual parts, tending to focus on the relationship of parts to and within the larger context, whole language proponents do not favor some types of phonics instruction. Interestingly, whole language advocates state that they do teach, and believe in, phonics, especially a type of phonics known as embedded phonics. In embedded phonics, letters are taught during other lessons focused on meaning and the phonics component is considered a "minilesson". Instruction in embedded phonics typically emphasizes the consonants and the short vowels, as well as letter combinations called rimes or phonograms. The use of this embedded phonics model is called a "whole-part-whole" approach because, consistent with holistic thinking, students read the text for meaning first (whole), then examine features of the phonics system (part) and finally use their new knowledge while reading the text again (whole). Reading Recovery is a program that uses holistic practices with struggling readers.Most whole language advocates see that children go through stages of spelling development as they develop, use and gain control over written language. Early literacy research conducted by Piagetian researcher, Emilia Ferreiro and published in her landmark book, Literacy Before Schooling, has been replicated by University of Alabama professor, Maryann Manning. Based on this research "invented spelling" is another "whole-part-whole" approach: children learn to read by writing in a meaningful context, e.g. by writing letters to others. To write a word they have to decompose its spoken form into sounds and then to translate them into letters, e.g. k, a, t for the phonemes /k/, /æ/, and /t/. Empirical studies[14] show that later orthographic development is fostered rather than hindered by these invented spellings - as long as children from the beginning are confronted with "book spellings", too.

Rise of whole language and reaction

After its introduction by Goodman, whole language rose in popularity dramatically. It became a major educational paradigm of the late 1980s and the 1990s. Despite its popularity during this period, educators who believed that skill instruction was important for students' learning and some researchers in education were skeptical of whole language claims and said so loudly. What followed were the "Reading Wars" of the 1980s and 1990s between advocates of phonics and those of Whole Language methodology, which in turn led to several attempts to catalog research on the efficacy of phonics and whole language. Congress commissioned reading expert Marilyn Jager Adams to write a definitive book on the topic. She determined that phonics was important but suggested that some elements of the whole language approach were helpful.[15][16] Two large scale efforts, in 1998 by the United States National Research Council's Commission on Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children[17][18] and in 2000 by the United States National Reading Panel,[19][20] catalogued the most important elements of a reading program. While proponents of whole language find the latter to be controversial, both panels found that phonics instruction of varying kinds, especially analytic and Synthetic Phonics, contributed positively to students' ability to read words on tests of reading words in isolation. Both panels also found that embedded phonics and no phonics contributed to lower rates of achievement for most populations of students when measured on test of reading words in isolation. The Panel recommended an approach it described as "scientifically-based reading research" (SBRR), that cited 5 elements essential to effective reading instruction, one of which was explicit, Systematic Phonics instruction (phonological awareness, reading comprehension, vocabulary, and fluency were the other 4).In December 2005 the Australian Government endorsed the teaching of synthetic phonics, and discredited the whole language approach ("on its own"). Its Department of Education, Science and Training published a National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy. [1] The report states "The evidence is clear, whether from research, good practice observed in schools, advice from submissions to the Inquiry, consultations, or from Committee members’ own individual experiences, that direct systematic instruction in phonics during the early years of schooling is an essential foundation for teaching children to read." Pg 11. See Synthetic phonics#Acceptance in Australia

State of the debate

Despite these results, many whole language advocates continue to argue that their approach, including embedded phonics, has been shown to improve student achievement. Whole language advocates sometimes criticize advocates of skill instruction as "reductionist" and describe the use of phonics as "word calling" because it does not involve the use of meaning. The United States National Reading Panel is criticized especially harshly by some in the whole language community for failing to include qualitative research designs that showed benefits for embedded phonics (the panel only considered experiments and quasi-experiments). On the other hand, some parents and teachers have objected to the de-emphasis on phonics in whole language-based curricula such as Reading Recovery and advocated their removal from schools.[21]Adoption of some whole language concepts

While rancor continues, much of whole language's emphasis on quality literature, cultural diversity, and reading in groups and to students is widely supported[who?] by the educational community. The importance of motivation, long a central focus of whole language approaches, has gained more attention in the broader educational community in the last few years. Prominent critic of whole language Louisa Cook Moats has argued, however, that the foci on quality literature, diversity, reading groups, and motivation are not the sole property of whole language.[22] She, and others[who?], contend these components of instruction are supported by educators of diverse educational perspectives. Moats contends that the properties essential to Whole Language, and those that render it ineffective and unfit for reading education are the principles that children learn to read from exposure to print, the hostility to drilling in phonics and other forms of direct instruction, and the tendency to endorse the use of context-clues and guess-work to decipher a word rather than phonemic decoding. In these and certain other tenets lie the essence and the error of Whole Language. Emphases on cultural diversity and quality literature is neither limited to Whole Language nor fundamental to it.Balanced Literacy

More recently, "Balanced Literacy" has been suggested as an integrative approach, portrayed by its advocates as taking the best elements of both whole language and code-emphasizing phonics, something advocated by Adams in 1990. The New York Public School system has adopted Balanced Literacy as its literacy curriculum, though critics of whole language have suggested that "Balanced Literacy" is just the disingenuous recasting of the very same whole language with obfuscating new terminology. Equally vociferously, the whole language advocates have criticized the United States National Reading Panel. Allington went so far as to use the term "big brother" to describe the government's role in the reading debate.[23]No Child Left Behind has brought a resurgence of interest in phonics. Whole language has thus during the 2000s receded from being the dominant reading model in the education field to marginal status, and it continues to fade.

Thinkers

Prominent proponents of whole language include Kenneth Goodman, Frank Smith (psycholinguist), Carolyn Burke, Jerome Harste, Yetta Goodman, Doroth

AUDIO LINGUAL METHOD

The audio-lingual method, Army Method, or New Key,[1] is a style of teaching used in teaching foreign languages. It is based on behaviorist theory, which professes that certain traits of living things, and in this case humans,

could be trained through a system of reinforcement—correct use of a

trait would receive positive feedback while incorrect use of that trait

would receive negative feedback.

This approach to language learning was similar to another, earlier method called the direct method. Like the direct method, the audio-lingual method advised that students be taught a language directly, without using the students' native language to explain new words or grammar in the target language. However, unlike the direct method, the audio-lingual method didn’t focus on teaching vocabulary. Rather, the teacher drilled students in the use of grammar.

Applied to language instruction, and often within the context of the language lab, this means that the instructor would present the correct model of a sentence and the students would have to repeat it. The teacher would then continue by presenting new words for the students to sample in the same structure. In audio-lingualism, there is no explicit grammar instruction—everything is simply memorized in form. The idea is for the students to practice the particular construct until they can use it spontaneously. In this manner, the lessons are built on static drills in which the students have little or no control on their own output; the teacher is expecting a particular response and not providing that will result in a student receiving negative feedback. This type of activity, for the foundation of language learning, is in direct opposition with communicative language teaching.

Replacement : Teacher : He bought the car for half-price. Student : He bought it for half-price.

Restatement : Teacher : Tell me not to smoke so often. Student : Don't smoke so often!

The following example illustrates how more than one sort of drill can be incorporated into one practice session :

“Teacher: There's a cup on the table ... repeat

Students: There's a cup on the table

Teacher: Spoon

Students: There's a spoon on the table

Teacher: Book

Students: There's a book on the table

Teacher: On the chair

Students: There's a book on the chair

etc.”[2]

In 1964, Wilga Rivers released a critique of the method in her book, The Psychologist and the Foreign Language Teacher. Subsequent research by others, inspired by her book, produced results which showed explicit grammatical instruction in the mother language to be more productive.[citation needed] These developments, coupled with the emergence of humanist pedagogy led to a rapid decline in the popularity of audiolingualism[citation needed].

Philip Smith's study from 1965-1969, termed the Pennsylvania Project, provided significant proof that audio-lingual methods were less effective than a more traditional cognitive approach involving the learner's first language.[3]

Butzkamm & Caldwell have tried to revive traditional pattern practice in the form of bilingual semi-communicative drills. For them, the theoretical basis, and sufficient justification, of pattern drills is the generative principle, which refers to the human capacity to generate an infinite number of sentences from a finite grammatical competence.[4]

This approach to language learning was similar to another, earlier method called the direct method. Like the direct method, the audio-lingual method advised that students be taught a language directly, without using the students' native language to explain new words or grammar in the target language. However, unlike the direct method, the audio-lingual method didn’t focus on teaching vocabulary. Rather, the teacher drilled students in the use of grammar.

Applied to language instruction, and often within the context of the language lab, this means that the instructor would present the correct model of a sentence and the students would have to repeat it. The teacher would then continue by presenting new words for the students to sample in the same structure. In audio-lingualism, there is no explicit grammar instruction—everything is simply memorized in form. The idea is for the students to practice the particular construct until they can use it spontaneously. In this manner, the lessons are built on static drills in which the students have little or no control on their own output; the teacher is expecting a particular response and not providing that will result in a student receiving negative feedback. This type of activity, for the foundation of language learning, is in direct opposition with communicative language teaching.

Charles Fries, the director of the English Language Institute at the University of Michigan, the first of its kind in the United States,

believed that learning structure, or grammar was the starting point for

the student. In other words, it was the students' job to orally recite

the basic sentence patterns and grammatical structures. The students

were only given “enough vocabulary to make such drills possible.”

(Richards, J.C. et-al. 1986). Fries later included principles for behavioural psychology, as developed by B.F. Skinner, into this method Example

Inflection : Teacher : I ate the sandwich. Student : I ate the sandwiches.Replacement : Teacher : He bought the car for half-price. Student : He bought it for half-price.

Restatement : Teacher : Tell me not to smoke so often. Student : Don't smoke so often!

The following example illustrates how more than one sort of drill can be incorporated into one practice session :

“Teacher: There's a cup on the table ... repeat

Students: There's a cup on the table

Teacher: Spoon

Students: There's a spoon on the table

Teacher: Book

Students: There's a book on the table

Teacher: On the chair

Students: There's a book on the chair

etc.”[2]

Historical roots

The Audio-lingual method is the product of three historical circumstances. For its views on language, audiolingualism drew on the work of American linguists such as Leonard Bloomfield. The prime concern of American Linguistics at the early decades of the 20th century had been to document all the indigenous languages spoken in the USA. However, because of the death of trained native teachers who would provide a theoretical description of the native languages, linguists had to rely on observation. For the same reason, a strong focus on oral language was developed. At the same time, behaviourist psychologists such as B.F. Skinner were forming the belief that all behaviour (including language) was learnt through repetition and positive or negative reinforcement. The third factor that enabled the birth of the Audio-lingual method was the outbreak of World War II, which created the need to post large number of American servicemen all over the world. It was therefore necessary to provide these soldiers with at least basic verbal communication skills. Unsurprisingly, the new method relied on the prevailing scientific methods of the time, observation and repetition, which were also admirably suited to teaching en masse. Because of the influence of the military, early versions of the audio-lingualism came to be known as the “army method.”[1]In practice

As mentioned, lessons in the classroom focus on the correct imitation of the teacher by the students. Not only are the students expected to produce the correct output, but attention is also paid to correct pronunciation. Although correct grammar is expected in usage, no explicit grammatical instruction is given. Furthermore, the target language is the only language to be used in the classroom.[1] Modern day implementations are more lax on this last requirement.Fall from popularity

In the late 1950s, the theoretical underpinnings of the method were questioned by linguists such as Noam Chomsky, who pointed out the limitations of structural linguistics. The relevance of behaviorist psychology to language learning was also questioned, most famously by Chomsky's review of B.F. Skinner's Verbal Behavior in 1959. The audio-lingual method was thus deprived of its scientific credibility and it was only a matter of time before the effectiveness of the method itself was questioned.In 1964, Wilga Rivers released a critique of the method in her book, The Psychologist and the Foreign Language Teacher. Subsequent research by others, inspired by her book, produced results which showed explicit grammatical instruction in the mother language to be more productive.[citation needed] These developments, coupled with the emergence of humanist pedagogy led to a rapid decline in the popularity of audiolingualism[citation needed].

Philip Smith's study from 1965-1969, termed the Pennsylvania Project, provided significant proof that audio-lingual methods were less effective than a more traditional cognitive approach involving the learner's first language.[3]

Today

Despite being discredited as an effective teaching methodology in 1970,[3] audio-lingualism continues to be used today, although it is typically not used as the foundation of a course, but rather, has been relegated to use in individual lessons. As it continues to be used, it also continues to gain criticism, as Jeremy Harmer notes, “Audio-lingual methodology seems to banish all forms of language processing that help students sort out new language information in their own minds.” As this type of lesson is very teacher centered, it is a popular methodology for both teachers and students, perhaps for several reasons but in particular, because the input and output is restricted and both parties know what to expect. Some hybrid approaches have been developed, as can be seen in the textbook Japanese: The Spoken Language (1987–90), which uses repetition and drills extensively, but supplements them with detailed grammar explanations in English.Butzkamm & Caldwell have tried to revive traditional pattern practice in the form of bilingual semi-communicative drills. For them, the theoretical basis, and sufficient justification, of pattern drills is the generative principle, which refers to the human capacity to generate an infinite number of sentences from a finite grammatical competence.[4]

I

DIRECT METHOD

he method refrains from using the learners' native language and uses only the target language. It was established in Germany and France around 1900. Characteristic features of the direct method are:

- teaching concepts and vocabulary through pantomiming, real-life objects and other visual materials

- teaching grammar by using an inductive approach (i.e. having learners find out rules through the presentation of adequate linguistic forms in the target language)

- centrality of spoken language (including a native-like pronunciation)

- focus on question-answer patterns

Principles

- Classroom instructions are conducted exclusively in the target language.

- Only everyday vocabulary and sentences are taught during the initial phase; grammar, reading and writing are introduced in intermediate phase.

- Oral communication skills are built up in a carefully graded progression organized around question-and-answer exchanges between teachers and students in small, intensive classes.

- Grammar is taught inductively.

- New teaching points are introduced orally.

- Concrete vocabulary is taught through demonstration, objects, and pictures; abstract vocabulary is taught by association of ideas.

- Both speech and listening comprehensions are taught.

- Correct pronunciation and grammar are emphasized.

- Student should be speaking approximately 80% of the time during the lesson.

- Students are taught from inception to ask questions as well as answer them.

Pedagogy

The key Aspects of this method are:I. Introduction of new word, number, alphabet character, sentence or concept (referred to as an Element) :

- • SHOW...Point to Visual Aid or Gestures (for verbs), to ensure student clearly understands what is being taught.

- • SAY...Teacher verbally introduces Element, with care and enunciation.

- • TRY...Student makes various attempts to pronounce new Element.

- • MO

The

Direct Method, also called the Natural Approach, developed towards the end of

the 19th century. It represents are critical

reaction to the teaching methods of the ancient Grammar Translation Method

which produced knowledge about language rather than knowledge of language. The

general goal of the Direct Method is to provide learners with a practically

useful knowledge of language. They should learn to speak and understand

the target language in everyday situations.

The

historical background to the call for a new approach to the teaching

of modern languages like French and English has both socio-economic and scientific

aspects. On the social and economic level the industrialization of western European

countries created a demand for a practically useful knowledge in subjects like

mathematics, physics, and modern languages. In Germany this gave rise to a new type of school called Realschule.

Unlike the traditional grammar schools the new type of school catered

mainly for children from the rising middle-classes. On the scientific side the

call for the teaching of living languages like French and English was accompanied

by the development of new linguistic approaches to the study of language. One

of the most prominent aspects of that development is the rise of phonetics and

phonology as a new linguistic discipline with the creation of the international

phonetic alphabet. At a time when teachers had no access to modern gadgets

like tape recorders or videos this provided them with the first sound information

on how to pronounce the target language words.

The

teaching methods recommended by the new reform movement followed logically

from the emphasis on providing a useful knowledge of target knowledge, because

that can only be developed by the direct use of the target language in class.

Rather than forcing learners to accumulate abstract knowledge about rules of

grammar, declensions and conjugations, with translations as a test of knowledge,

reformers proposed that the target language should be learnt like children learn

their first language, that is by using it in class.

This is why the new approach is known as the Natural Approach or the Direct

Method. Typical of the new teaching methods is the use of chains of activities

accompanied by verbal comments like: I go to the door. I open the door. I

close the door. I return to my place. I sit down. They are also called Gouin

Series after the French reformer Gouin. There can be no doubt, however, that given the

general authoritarian attitude to education typical of the 19th century

teachers remained very much in command and all teaching was very much teacher

centred.

There

was a marked change in teaching contents, however. The emphasis was now

on knowledge of words and phrases useful for everyday life, and of factual

knowledge about the target language country, its geography, major cities,

industry, etc. In contrast to that the reading of great literary

texts by the greatest authors, which is typical of the Grammar Translation Method,

was given no priority. Note, however, that the still strong and influential

faction of grammar school teachers considered this a debasing of the high principles

of good education, and eventually many reformers were willing or forced to compromise

when they fought for recognition of the new type of Oberrealschule

as institutions entitled to issue school living certificates that granted

access to university studies and were equal in status to grammar school diplomas.

It is important to note this because for many years to come classroom reality

was characterized by a mixture of methods and goals of teaching that had their

origin no less in ancient grammar translation methods than in the reformist

concepts of the Direct Method.

Historically, the word content has changed its meaning in language teaching. Content used to refer to the methods of grammar-translation, audio-lingual methodology and vocabulary or sound patterns in dialog form. Recently, content is interpreted as the use of subject matter as a vehicle for second or foreign language teaching/learning.

Benefits of content based instruction

1. Learners are exposed to a considerable amount of language through stimulating content. Learners explore interesting content & are engaged in appropriate language-dependant activities. Learning language becomes automatic.2. CBI supports contextualized learning; learners are taught useful language that is embedded within relevant discourse contexts rather than as isolated language fragments. Hence students make greater connections with the language & what they already know.

3. Complex information is delivered through real life context for the students to grasp well & leads to intrinsic motivation.

4. In CBI information is reiterated by strategically delivering information at right time & situation compelling the students to learn out of passion.

5. Greater flexibility & adaptability in the curriculum can be deployed as per the students interest.

Comparison to other approaches

The CBI approach is comparable to English for Specific Purposes (ESP), which usually is for vocational or occupational needs or English for Academic Purposes (EAP). The goal of CBI is to prepare students to acquire the languages while using the context of any subject matter so that students learn the language by using it within the specific context. Rather than learning a language out of context, it is learned within the context of a specific academic subject.As educators realized that in order to successfully complete an academic task, second language (L2) learners have to master both English as a language form (grammar, vocabulary etc.) and how English is used in core content classes, they started to implement various approaches such as Sheltered instruction and learning to learn in CBI classes. Sheltered instruction is more of a teacher-driven approach that puts the responsibility on the teachers' shoulders. This is the case by stressing several pedagogical needs to help learners achieve their goals, such as teachers having knowledge of the subject matter, knowledge of instructional strategies to comprehensible and accessible content, knowledge of L2 learning processes and the ability to assess cognitive, linguistic and social strategies that students use to assure content comprehension while promoting English academic development. Learning to learn is more of a student-centered approach that stresses the importance of having the learners share this responsibility with their teachers. Learning to learn emphasizes the significant role that learning strategies play in the process of learning.

Motivating students

Keeping students motivated and interested are two important factors underlying content-based instruction. Motivation and interest are crucial in supporting student success with challenging, informative activities that support success and which help the student learn complex skills (Grabe & Stoller, 1997). When students are motivated and interested in the material they are learning, they make greater connections between topics, elaborations with learning material and can recall information better (Alexander, Kulikowich, & Jetton, 1994: Krapp, Hidi, & Renninger, 1992). In short, when a student is intrinsically motivated the student achieves more. This in turn leads to a perception of success, of gaining positive attributes which will continue a circular learning pattern of success and interest. Krapp, Hidi and Renninger (1992) state that, "situational interest, triggered by environmental factors, may evoke or contribute to the development of long-lasting individual interests" (p. 18). Because CBI is student centered, one of its goals is to keep students interested and motivation high by generating stimulating content instruction and materials.Active student involvement

Because it falls under the more general rubric of communicative language teaching (CLT), the CBI classroom is learner rather than teacher centered (Littlewood, 1981). In such classrooms, students learn through doing and are actively engaged in the learning process. They do not depend on the teacher to direct all learning or to be the source of all information. Central to CBI is the belief that learning occurs not only through exposure to the teacher's input, but also through peer input and interactions. Accordingly, students assume active, social roles in the classroom that involve interactive learning, negotiation, information gathering and the co-construction of meaning (Lee and VanPatten, 1995). William Glasser's "control theory" exemplifies his attempts to empower students and give them voice by focusing on their basic, human needs: Unless students are given power, they may exert what little power they have to thwart learning and achievement through inappropriate behavior and mediocrity. Thus, it is important for teachers to give students voice, especially in the current educational climate, which is dominated by standardization and testing (Simmons and Page, 2010).[1]Conclusion